Translation.

I used Culhwch and Olwen by Rachel Bromwich and D. Simon Evans, published by the University of Wales Press, 1992. It is a magnificent work of scholarship. I have given daily thanks for the good people who made Geiriadur Prifysgol Cymru (GPC) freely available online.

The linguistic problems facing anyone trying to translate medieval Welsh are documented elsewhere.

I took everything I knew about translation theory, put it in a box, and buried it where I couldn’t find it. When I began translating this story I thought the Court List, the List of Tasks, and the Great Boar Hunt. would present too much of a challenge to my Model Reader who doesn’t read medieval or modern Welsh.

My initial plan was to shorten the Tasks to only those which occur in the story, cut the Court List altogether and keep the Hunt to a minimum.

I changed my mind about all three.

The Court List:

‘I ask you to get me Olwen,

daughter of Ysbaddaden Pencawr.

And I invoke her in the name of your warriors,

calling on them to witness your promise.’

Culhwch then launches into a list of all the names of the warriors at Arthur’s court.

Reasons to cut it.

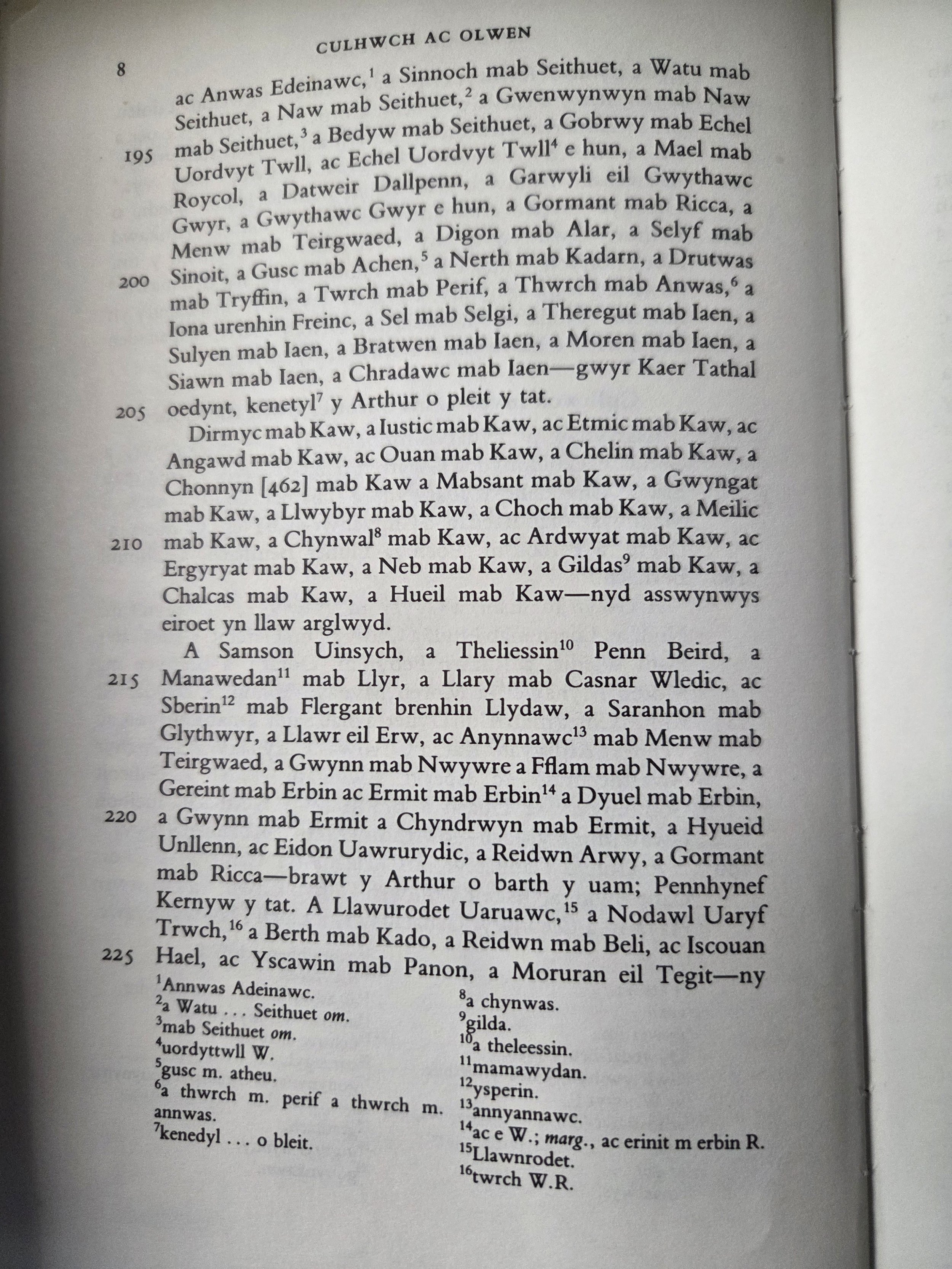

It’s essentially a list of names, with attributes attached to some of them. It runs for four pages or two hundred lines in the Bromwich and Evans edition. The editors count ‘about 260’ names. It begins like this:

Culhwch invoked his boon in the name of Kei and Bedwyr, and Greidawl Galldouyd, Gwythyr mab Greidawl, Greit mab Eri, Cyndelic Kyuarwyd, Tathal Twyll Goleu, and

Malwys mab Baedan and Chnychwr mab Nes, and Fergus m Poch, and Lluber Beuthnach and Chonul Bernach.

The decision anyone translating the story has to make is what to do with the names.

The list rolls and heaves, building rhythm and pace. The storyteller became so caried away with the rhythm that in places it feels as though he’s inventing names to keep the beat. Some of those names, like Suck son of Sucker, are part of the humour of the list.

To keep the rhythm and sound involves leaving the names in Welsh. Not only might the non Welsh speaker be daunted by the pronunciation, but they will miss the humour of the list. The temptation is to play Alexander the Great and not try and unravel the knot but cut it.

Bromwich and Evans suggest; ’But if the whole series of names between lines 175-373 is excised, the tale runs on with greater clarity and smoothness: line 174 being followed immediately by line 374.’ They are right, of course:

‘I ask you to get me Olwen,

daughter of Ysbaddaden Pencawr.

And I invoke her in the name of your warriors,

calling on them to witness your promise.’

[Delete 200 lines of text]

‘Ah, Chieftain,’ said Arthur,

‘I’ve never heard of this maiden,

nor her family. But, I will gladly

send messengers to find her.’

Reasons to Include the List:

Plot isn’t everything. Deciding on what is relevant to a story is not a straightforward process regardless of what your editor claims. Relevant to your reading or mine or to a possible reading neither of us have made? James Joyce and Umberto Eco would have loved it. So what might it add to the story?

The court list demonstrates the extent of Arthur’s power. It contains men from France, Ireland, Brittany and the Uplands of Hell, as well as bishops, kings and the sons of kings. It contains historical figures, euhemerised characters from earlier myth, and figures from other story cycles.

Arthur’s court might be impressive, but we know it falls, and the list forcibly reminds us of this by referring to the battle of Camlann. We meet one of the nine men who planned the battle, and the three men who escaped. Even the mention of Gwyhenever and her sister alludes to the fact that, according to the Triad, Camlann was the result of her sister hitting the queen. There is also the man who will kill Kei, who Arthur will kill in revenge.

The absurd qualities of some of the heroes are exaggerated exaggerations: the kind I heard growing up: he could eat you out of house and home; he drinks so much his legs must be hollow; he can talk the hind legs off a donkey. So they don’t feel as alien as they might and I enjoy them. The fact that so many of these names have special skills or qualities, even when the skills and qualities are absurd, emphasises the fact that Culhwch has nothing going for him other than his fine horse, his shiny weapons, and his bad manners. He is out of his depth even before Ysbaddaden stipulates 40 Impossible Tasks.

The list also reinforces the fact that neither Culhwch nor reader, nor the original audience, are in familiar territory anymore. Once Culhwch has been greeted by the porter we’ve entered a very different version of the world. By the time we reach the end of the court list, the relative sanity of the opening of the story with its folk tale style familiarity is forgotten. The list acts as a portal that normalises the rest of the story. Once we've passed through it, nothing that follows seems strange.

You can also feel the storyteller working the audience. As he launches into the list, the audience would tense. How long will this go on for? But they will never know what comes next, if it’s serious or ludicrous, and the variation carries them through on surging rhythms. It’s an essential part of the performance that is this story. It would have been an outstanding feature of an oral performance, a high stakes act with a huge payoff if he didn’t do the equivalent of falling flat on his face.

The invented names in the list remind us there was a time when names had meaning. To take a random example from a book on Medieval Hunting (by John Cummings): Jehan Corneprise’ (John blow the death), Jehan Ievre (John Hallo-the-hare) and Huelguillot le Mastiner (Guillot the mastiff man.)[i]

The story teller thought Culwch meant ‘Pigsty’ and Olwen ‘white track’ and may have been wrong about both. Names are either followed by a patronymic, rarely a matronymic, or an epithet. The storyteller treated these conventions with respect, but also as an opportunity for invention.

All names meant something, but I only translated the ones where the writer was obviously playing. I didn’t include all the names but I didn’t leave out many.

The list is entertaining and serves a structural purpose.

The Anoethau[ii]

This is the second problem sequence.

The giant Ysbaddaden gives Culhwch forty impossible tasks which are referred to by the editors and within the text as Anoethau.[ii]

After Ysbaddaden stipulates the first task, Culhwch replies:

Hawd yw gennyf gaffel hynny, yd tybyckych na bo hawd.

‘I can get that easily, ‘though you may think I can’t.’

Ysbaddaden responds:

Kyt Kffych hynny, yssit ny cheffych.

‘Though you might get that, there’s something you won’t.

Each subsequent task is wrapped by these lines. Both phrases are repeated approximately forty times, which is repetition driven to excess. Would it be too much to ask of a modern reader?

I was tempted to cut the list of tasks down to only those which are performed in the story, which is roughly ten of them.

However.

Perhaps anachronistically, we can see the dialogue that develops in dramatic terms. It is a clash between two characters who have irreconcilable objectives. As a result of this exchange, one of them must die.

Culhwch knows he will never marry anyone except Olwen. He’s been told several times that most men who come on the quest to marry her have been killed. There are initially three visits to Ysbaddaden. In each, the giant sustains injuries that should have killed him. The unstated implication is that Ysbaddaden can’t be killed until his daughter ‘goes with a man’.

Ysbaddaden is understandably inhospitable to any suitor. For unstated reasons, he seems compelled to enter a contract with the suitor and offer him the opportunity to complete an impossible task. If the suitor flinches or fails, the giant can kill him.

The dialogue begins with Ysbaddaden stating an obvious impossibility. He wants a field cleared, ploughed, sown and the resultant crop reaped all in one day. Instead of protesting, Culhwch, says: ‘I can get that easily, ‘though you may think I can’t.’

Perhaps wondering if the boy has understood, the giant then explains why it is impossible: you need this man to prepare the field, he won’t do it of his own free will, and you can’t make him. Culhwch repeats his phrase. You also need this man to fix the plough and he won’t come and you can’t make him. And Culhwch, like a naked man in a hailstorm, refusing to flinch, repeats: ‘I can get that easily, ‘though you may think I can’t.’

And so on. Things needed for the wedding feast; things needed to prepare and shave his beard; dogs, people, horses and objects needed to hunt the Twrch Trwyth.

Ysbadadden keeps going, waiting for the boy to crack, and Culhwch stands his ground and repeats the same response. He’s hiding behind it because, of course, he can’t achieve any of these things. He's just a rich pretty boy with bad manners and shiny toys.

As the boy refuses to crack, Ysbaddaden must see his own death coming towards him. He plays his final card. It’s obvious the boy can’t do any of these things on his own.

‘Though you might get that, there’s something you won’t get.

Arthur and his men to hunt Twrch Trwyth.

He is a powerful man with many kingdoms.

He will not come, and why not, because he’s in my hand.’

‘ But Culhwch still refuses to flinch, still repeats his line. The giant, running out of ideas, reaches for absurdity, a desperate explosion of nonsense. He’s been pounding away, and now he must realise that he’s been punching the side of a mountain.

Then he makes one final attempt, saying what they both know:

Sleeplessness without rest you will get in seeking these things,

and you won’t get them, and you won’t get my daughter.

But Culhwch, who has already shown he’s not the most tactful or polite of young men, now sticks the boot in:

Horses and hounds I will get.

And Arthur,

my lord and kinsman,

will get everything for me.

And I will have your daughter,

and you shall lose your life.

I think the dialogue has a structural coherence and a dramatic context, but whether that underlying drama is strong enough to carry a modern reader through the repetition remains to be seen.[iii]

The hunting of the great boar, Twrch Trwyth,

Arthur gathered the hosts,

of the three Islands of Britain,

and her three adjacent islands,

and of Brittany, Normandy,

and the Summer country

And let it be proclaimed,

the hunting of the hog,

has been sung by David Jones

and neither Taliesin nor Aneirin

nor Dafydd ap Gwilym himself

the Early Bards,

the Not So Early bards,

the Poets of the Princes,

the Poets of the Well to Do

the keepers of old lore, or

the skilled translators of his vanished tongue,

(loving this story in elegant prose translations)

nor modern experts in the intricate cynghanedd

nor any poet of that other language,

could sing it better.

My recording of The Hunt by David Jones is here:

http://www.liamguilar.com/the-poetry-voice/2019/4/2/david-jones-the-hunt

There’s a recording of David Jones reading The Hunt with a short introduction here:

https://bebrowed.wordpress.com/2014/03/17/david-jones-reads-the-hunt/

David Jones’ ‘The Hunt’, is not a translation but a response. It is magnificent. It offered one possible way to deal with the episode. Translating it, I realised it is a magnificent piece of writing, which moves to its own rhythm. I left nothing out.

[i] The translations are Cumming's. The Art of Medieval Hunting:the Hound and the Hawk. Castle books 2003.

[ii] GPC offers: wonderful thing, wonder, jewel, treasure; something difficult to obtain or achieve, feat, exploit; wondrous, wonderful, strange, unusual,?difficult.

[iii] When I started working through the Tasks I read. Fiona Dehghani’s. “The Anoetheu Dialogue in Culhwch Ac Olwen.” Proceedings of the Harvard Celtic Colloquium, vol. 26/27, 2006, pp. 291–305. JSTOR,http://www.jstor.org/stable/40732062.) It argues the same point.