John Dressel (b1934)

I worry about my pronunciation of people’s names, so if I have mispronounced John Dressel’s I apologise.

Like Hamlet (see previous episode) Goliath has escaped his story.

Recently a news headline read; ‘Firm wins in David and Goliath legal battle’.

The writer of the headline was confident that the reader would know that this meant a battle between a small firm and a much bigger one. The writer was also positioning the reader to see the smaller as heroic and admirable, and the bigger as the bad guy in the case.

The story of David and Goliath has entered into popular discourse, and people who have never read the Bible know enough to make sense of that headline.

But there’s no reason why we should automatically sympathise with David, or with every small entity taking on a larger one. Dressel’s poem makes this point, playfully.

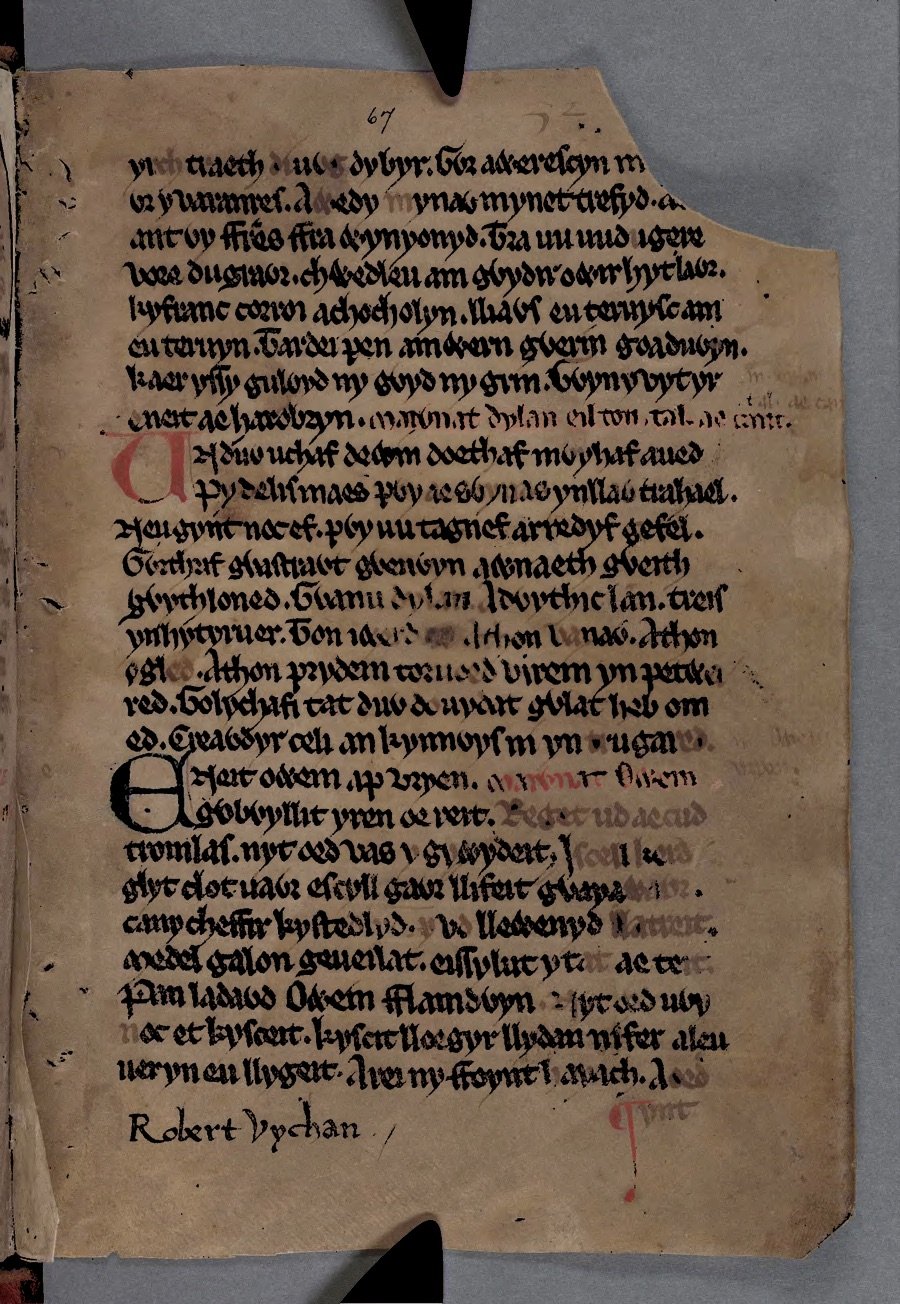

This poem is taken from ‘Twentieth Century Anglo-Welsh Poetry’ edited by Dannie Abse and printed by Seren/Poetry Wales Press 1997, reprinted 1998.