Plodding onwards, now in Ystoria Gereint Uab Erbin, I am still in awe of the story teller’s skill.

He walks such a fine line between a minimalist narration that would be the envy of Raymond Carver and notes for a story he hasn’t written.

Here’s the incident that kick starts the story ‘Gerient Son of Erbin’. The quotes are taken from Sioned Davies' impressive translation.

A Forester has approached Arthur at the feast, and after the formal greetings:

‘Tell us your news’ said Arthur.

‘I will Lord,’ he said. ‘A stag have I seen in the forest and I have never seen anything like it.’

‘What is it about it for you never to have seen anything like it?’ said Arthur

‘It is pure white, lord, and it does not walk with any other animal out of arrogance and pride because it is so majestic. And it is to ask you advice lord, that have I come. What is your advice in the matter?”

‘I shall do the most appropriate thing,’ said Arthur, ‘and go and hunt it tomorrow at dawn; and let everyone in the lodgings know that, and Rhyferys (who was a chief hunstman of Arthur’s) and Elifri (who was the chief squire) and everyone else’.

The speech isn’t ‘described’. The same verb is used every time. The speaker is identified, but how he (or she in other instances) speaks is left to the audience. ‘Tell us your news’ said Arthur. Bluntly? In a resigned tone? In an authoritarian manner?

It’s up to you.

There is no need to indicate who is being spoken to. ‘Let everyone know’ is obviously not addressed to the Forester. But ‘Arthur turned to his court officials and said’ would be redundant.

There’s no description of what’s happening in the background during the conversation either. Nor is there any description of Arthur’s reaction, (there’s no description of Arthur), but I think you can hear him lean forward, suddenly paying attention at ‘I have never seen anything like it’. And you can hear the courtiers nearby voicing their approval when after ‘the most appropriate thing’ Arthur says ‘I will go and hunt it’.

The style invites the audience in and asks it to participate, but also gives it the freedom to make it its own.

I like this very much. It reminds me of the best of the traditional ballads, where everything that isn’t essential has been stripped out. You could argue that it produces too much ambiguity? Is Arthur bored or annoyed or excited? And the answer is probably that it’s not as important as what he says. You could argue that the style is the product of an exterior world, and we live in one that likes to pretend it has access to intention, character and emotion. And a great deal of modern fiction is based on the convention that the writer not only can but in some ways is obliged to tell you what the character/s is/are thinking. But it’s one of modern literary fictions more dubious characteristics.

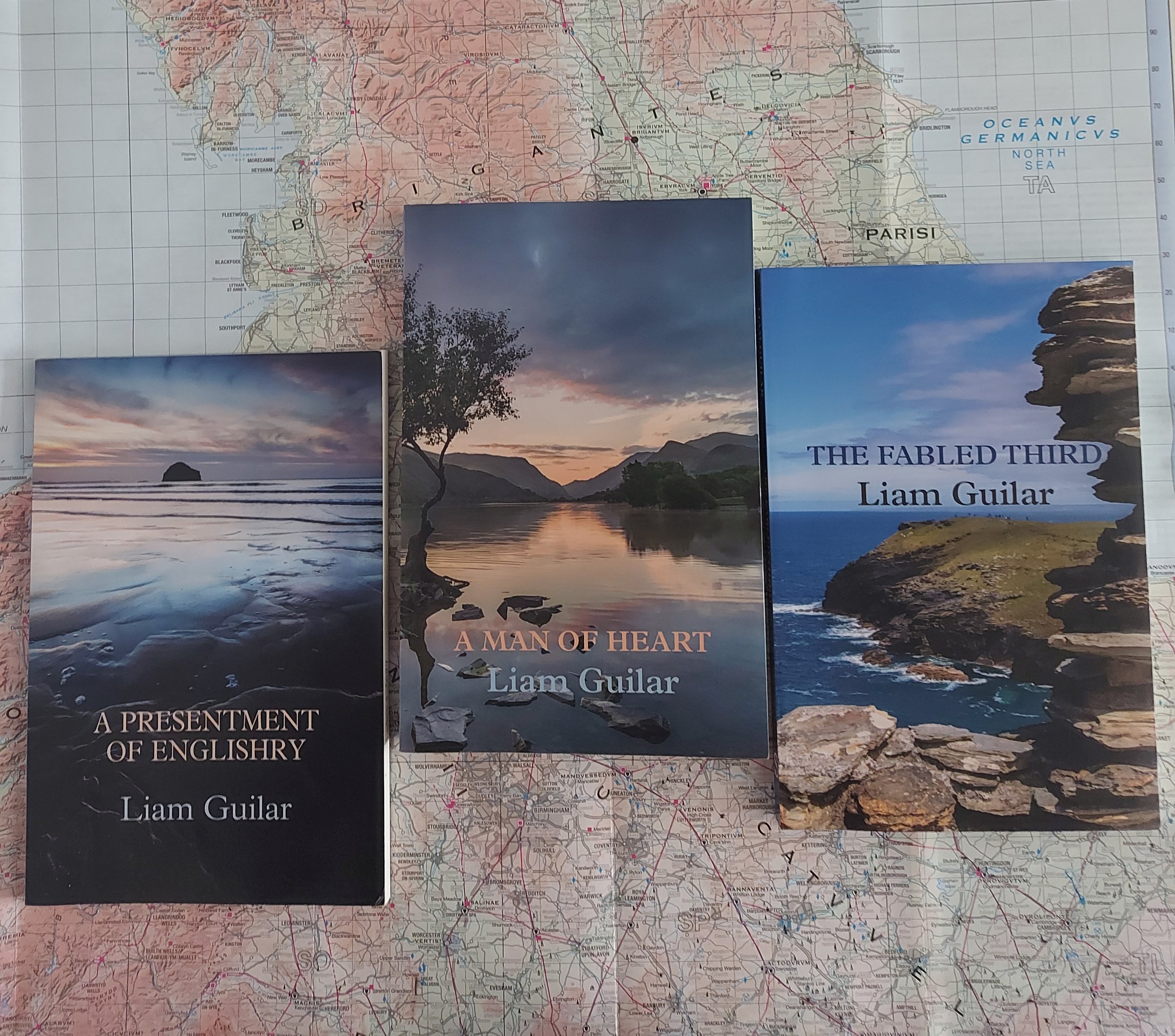

I'm at the editing end of the current writing project. The next part of A Presentment of Englishry is almost finished. I’m weighing up how much I can cut out. I’d like to follow the medieval method, but I suspect most modern audiences would not be happy with such a minimalist approach.

On the other hand.

I’m not so enamoured by the story-teller’s habit of describing what people are wearing. This happens to a greater or lesser extent across all the stories I’ve translated so far, and I’m beginning to assume there will be curly auburn hair, tunics and surcoats, brocaded silk and boots of Cordovan leather. In a status conscious world clothes are obviously a mark of status. But it seems there wasn’t much variation available.

The Forester who speaks above is described as:

A tall auburn haired lad, wearing a tunic and surcoat of ribbed brocaded silk, and a gold hilted sword around his neck, and two low boots of Spanish leather about his feet.

60 lines later, Gereint is described on his first appearance in almost identical terms, when he’s seen by Gwenhwyuar and her maid as they are trying to catch up with Arthur and the hunt.

A young bare-legged, auburn-haired noble squire with a gold hilted sword on his thigh, wearing a tunic and surcoat of brocaded silk with two low boots of Spanish leather on his feet and a mantle of blue purple over that with a golden apple in each corner.

You’d be forgiven for thinking the story has just got interesting and the forester is riding after Gwenhwyuar. Instead it’s an encounter with one of the story teller’s limitations.

But they tend not to outweigh his strengths.